Small Steps Can be a Big Thing – Shooting a Short Film on a DSLR Camera

Daddy Day - A short film

For a man who works in the New York City film industry, Eric Scherbarth, AKA daddy, remarks that his short film creation “Daddy Day” was one of the smallest productions he’s ever done in terms of crew size. “It was just me on camera and lights, my wife as baby-wrangler and a couple of friends as grips.” And of course there was his co-star Brandon, age 11 months.

Scherbarth’s entry, “Daddy Day,” was just one of more than 500 submissions uploaded to the Nikon Everyday Cinema competition. Entrants were tasked with creating a cinematic short that profiled an everyday moment. “Daddy Day” was recognized with an Honorable Mention award.

Storyboards Not Essential

When it comes to initiating a cinematic creation everyone has a different method for approaching the task. As a rule, Scherbarth prefers to not use storyboards. “A lot of the joy for me comes from simply showing up on the set, then exploring angles and blocking with the camera and your actors. The few times I have used storyboards I felt they did nothing but limit me to shots I had arbitrarily constructed in my head.”

Spontaneity more his style, Scherbarth had begun conjuring up his Nikon short as a cartoonish fun romp; but not long afterwards a producer’s epiphany hit: “My son and I were playing in the bedroom. I briefly stepped around the corner to throw something in the trash. It was only a few seconds, but by the time I returned he had somehow removed a fishing knife that I had haphazardly placed in an end table. He was holding it with his bare hands! Miraculously he did not injure himself.” That moment basically summed up a re-envisioned “Daddy Day” plot line.

Nikon D600 on set of “Daddy Day” film shoot.

“To me, the best shorts are structured like a joke: you have the set-up, punchline and topper,” explains Scherbarth. “With the piece being a not-so-subtle reference to the ‘Dawn of Man’ sequence in Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, I knew from the beginning I was going to incorporate the music from Thus Spoke Zarathustra. I also knew I was going to elongate the baby’s first step sequence with slow motion, and that the production was going to culminate in the slap-sticky punchline of the father catching the iron.” With a goal to pack all of this into less than three minutes, Scherbarth reasoned he’d need to establish the set-up and the topper (“So you’re walking now”) very quickly and economically.

Point of View from a Camera Operator

The 137-second “Daddy Day” packs ample camera operator technique—which makes it a worthy candidate for analysis. Using his Nikon full frame DSLR, Scherbarth opens in landscape view to establish the scene. Footage then immediately cuts in closer, bringing the viewer tight with the main characters. Within seconds a third camera angle offers a close-up to explain what the main character, dad, must do when he steps away for a few moments.

Just 20 seconds into the short film with dad out of the picture, and script foreshadowing the likely role that iron and ironing board will play, the camera now focuses on Brandon. At this time the director goes to work on our emotions—parading innocence, curiosity and achievement—all the while building tension and sense of danger. Scherbarth uses varied point-of-view shots, slow motion footage, panning techniques, soft focus and intentional close-ups on small details that matter most and move the story forward.

Cut to dad occupied a few steps away and then, just in the nick of time, dad lurches toward Brandon, he himself taking the brunt of the danger. We do not see his agony, but hear it when the camera goes to a wide angle view from outside the home. In the final frame all is well. Brandon and dad share a drink in front of the television. The resolve is obvious, the dialogue campy and baby’s first steps have been made all the more memorable.

Calling up his director’s mind, Scherbarth shares, “I think a key technique is to smoothly establish and transition to your characters’ points of view. I generally ease into any initial obvious point-of-view shots (such as the phone and iron inserts) by sandwiching those shots between close-ups of the character who provides the point-of-view.” Furthering, he adds that when switching from one character’s point of view to another’s (the daddy to the baby), he likes to cut back to a wide shot with the goal of reestablishing geography for the scene. Then, Scherbarth cuts to the next character’s close-ups via shots from their point-of-view.

Continuing, “For this style of camera work I like a faster prime lens. I may be switching lenses a lot, but I’ve found it to be worthwhile. Primes can be much more sharp versus a lens with range. You can also detect a noteworthy difference in look between an f/2.8 and an f/1.4 lens.”

Nikon D600 on set of “Daddy Day” film shoot.

A Fraction of the Size and Weight

Compared to previous films he’s produced using video cameras and 35mm adapter/lens systems, Scherbarth was happy to work with a camera that was a fraction of the size and weight to which he’s accustomed. “The far smaller and lighter Nikon D600 still got me that filmic shallow depth-of-field look that I love, plus the added benefit is the camera’s full frame sensor,” he points out. “That large sensor translates to less reliance upon external lighting. I was able to work without a lot of distracting clutter. I was able to focus on the important element—constructing a story.”

Working with an ultra-lite Nikon DSLR as placed on a tripod with a fluid head, the director’s capture was acquired using either an f/2.8 or an f/1.4 lens. When essential for indoor work, he tapped a 1×1 LED lite panel to add flair or put a sparkle into his son’s eye.

The camera’s Picture Control setting was dialed to Neutral. He then adjusted down the contrast even more. Scherbarth says that doing this is not unlike assigning a Cine picture profile in a dedicated video camera. “It gives you a rather flat look, but the idea is to capture as much information as possible so you have more leeway in post.” Another must is finding ways to not blow-out the whites. “I usually try to capture in lower luma ranges to avoid the blow-out from happening. It’s easy to push the highlights and crush the shadows in post.”

Most of the filming was completed in a room that receives very little direct sunlight. Plus, with acquisition done on overcast days, he found himself relying on bounced and filtered light. “I rarely used any lights; and when I did, I did it for style.”

Actor in Charge

With all his point-of-view, variety of focus, plus work in minimal lighting, one would think camera operation to be Scherbarth’s most challenging element. Not so.

“By far the most taxing thing was getting the baby to do what I wanted him to do,” he grins. “I watch Brandon twice a week by myself so I know first-hand how difficult it can be to manage him or keep him still. Brandon has just about zero tolerance for taking direction, and that day needed to take breaks more often than the worst of divas.”

But success on-set prevailed when he and his wife busted out a laser pointer. “That laser was the only thing he could fixate on for more than three seconds. By aiming it around we could get him to look and walk in the directions we needed.” Thank goodness for that one small prop. Without it, “Daddy Day” may not have been such fun.

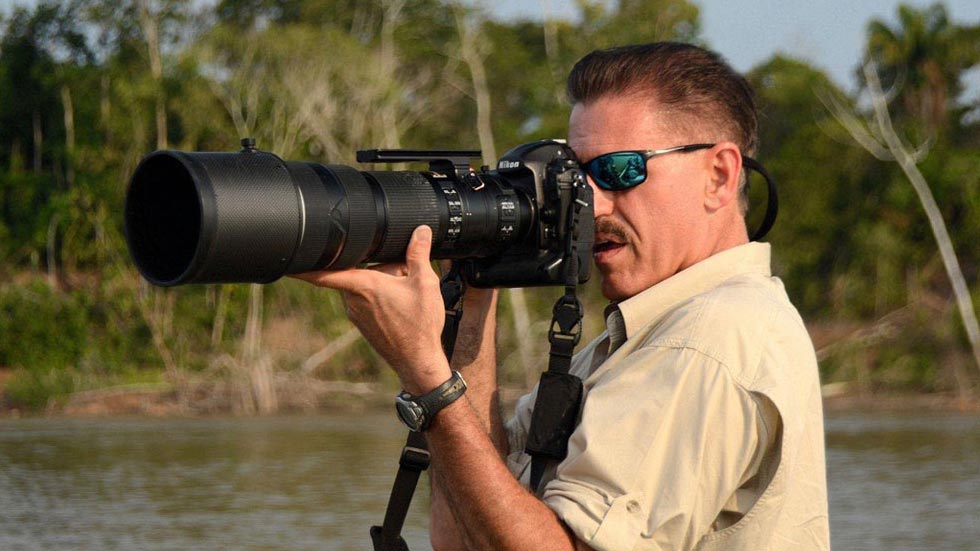

Eric Scherbarth, Director on set of “Daddy Day” film shoot.

Tips

-

For instances when you cannot shoot in lower luma ranges (to avoid blowing out the highlights), but have shots where high luma ranges are unavoidable (such as sunny exterior shoots), try underexposing by half a stop or even a full f/stop. This will retain as much detail as possible in the highlights; you can then push the midtones in post.

-

If you plan to edit with software and speed up or slow down footage, shoot at 60fps. Those extra frames give the program more to work with. Footage will look much more smooth and natural, and appear less glitchy than capture shot at 24fps or 30fps.

-

If you have a camera that can switch between FX and DX modes this can come in handy for run-and-gun situations. For example, if I can’t get close enough to the action and don’t have time to switch lenses, I switch to DX mode to bring me closer; the resolution quality is unaffected for video. I also find that shooting in DX mode gives more focusing leeway. True, the shallow depth-of-field that full frame cameras achieve does look beautiful, but sometimes it’s challenging to maintain focus in FX mode—especially in low-light situations where stopping down is impossible and your subject is moving.

-

Consider using LED lights. They are light, easy to use and give off hardly any heat. They provide a nice soft light similar to Kino Flos but are far less cumbersome.